In a blog post yesterday, Verizon fired the latest round in the public blame wars over why Netflix videos buffer on their network. The case they made offered little new information, however, and of course placed the blame squarely upon Netflix.

The interconnection deal between the two companies is still being implemented, however it has not stopped the blame game. Last month Netflix went so far as to have its service pop up a message to consumers citing Verizon’s ‘crowded’ network for problems. Verizon was decidedly not happy with this development, which exposed the one weakness they have as the last mile network owner — the contentious relationship that already exists between them and the consumer.

But Verizon’s blog post covered only familiar territory to those familiar with the situation. They argue that Netflix is using transit connections that can’t handle the volume, that the traffic is asymmetric and therefore it is not their responsibility to update peering connections, and that if Netflix or the transit network would just pay for the right to connect to Verizon’s network there would be no traffic problems at all.

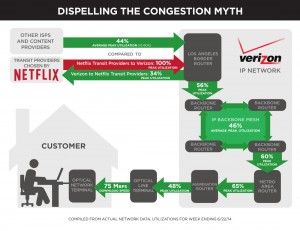

They provided this helpful graphic showing that everything works exactly the way it should except the connection to transit networks. Of course, the only people disputing this are the side of the media that don’t understand networks. The problem has always been at the point of interconnection, and the real dispute remains over who pays who and why for the traffic that passes through it and the upgrades required to do it.

They provided this helpful graphic showing that everything works exactly the way it should except the connection to transit networks. Of course, the only people disputing this are the side of the media that don’t understand networks. The problem has always been at the point of interconnection, and the real dispute remains over who pays who and why for the traffic that passes through it and the upgrades required to do it.

Verizon sells explicitly asymmetric bandwidth to consumers that it knows will download more than they upload, then complains that the traffic they get from the outside world is asymmetric and therefore not their problem. Meanwhile, Netflix makes the case that it shouldn’t pay anything at all for mere network infrastructure, and is busy trying even to cut the transit providers and CDNs themselves out of the loop entirely with its own content delivery infrastructure.

Neither is giving an inch yet, and none of it makes sense except to the spinmeisters. But to me the real question is why it is taking so long to implement the direct connection between Verizon and Netflix that was announced months ago. In a world where we’re talking about on-demand bandwidth and SDN in the WAN, the idea that it will take the rest of 2014 for something we’ve known how to do since the 90s is just silly. Hell, they fixed Obamacare’s website issues faster, and that was the government.

If you haven't already, please take our Reader Survey! Just 3 questions to help us better understand who is reading Telecom Ramblings so we can serve you better!

Categories: Internet Traffic · Video

…exactly right…..the contentious relationship VZ has with their customers has always been an issue. They are the worst to deal with from a consumer or business standpoint. It is like they don’t care and don’t mind if you know it.

Given their response to Netflix’s move last month, I’d say it turns out that they do mind.

Having spent a bit of time embroiled in this issue, I would note:

-Arguing esoteric asymmetric traffic ratios or the nuances of interconnection is interesting to industry insiders but does not address the central issue

-This is fundamentally an anti-trust question. If VZ operates in a competitive market, they can charge whatever they choose. If the market is constrained, then VZ cannot use a bottleneck facility to disadvantage competitors.

-I would note that FCC studies indicate that in 70% of markets, consumers have little or no choice when purchasing local internet access capable of supporting full screen streaming video.

Jim (wink wink) –

Bottlenecks, Shmottlenecks…what most everyone is more interested in is when LVLT will get to $100/share?

us suckers who got the broomhandle up the hoo haa at tw are wondering that, too!

What speed is being used for this? It barely takes a couple megs to do full screen NetFlix or YouTube.

the image isn’t clickable, which is trivial but still maddeningly annoying.

Sorry about that, it is now clickable.

When Verizon makes noise about asymmetric volumes, I scratch my head in bemusement. ILECs have played the asymmetric traffic gambit once before and got badly burned, that is until they begged and convinced regulators to change the rules in their favor.

Before the king’s men put together Humpty Dumpty again to create Verizon (Bell Atlantic & NYNEX and GTE, technically not a baby bell) and ATT (SBC, BLS, Ameritech & PacBell), there existed 7 not so baby siblings. (US WEST was bought out by CenturyLink.)

These baby bells, circa 1993-1995 spent an inordinate amount of time and money trying to keep CLECs like TCG, MFS, MCI Metro, Brooks Fiber and others from effectively entering and competing in the local exchange business.

This period actually began in earnest around 1993. What is very important to understand about this tale is that local portability (LNP) did not exist. In fact, the first LNP implementation was Chicago, 1998. This meant that prior to 1998 if a CLEC won a local exchange customer (e.g., Merrill Lynch or Fidelity), EVERY employee would have to change their phone number. So the hill these CLECs had to climb began quite steep.

Although some very kluge number portability workarounds had been proposed (e.g., remote call forwarding or RCF), the ILECs rejected them or set the RCF rates for CLECs prohibitively high. So the CLECs, instead, pushed for the easier sale with customers, Direct Outward Dial (DOD) service which allowed Merrill and Fidelity, for example, to keep their phone numbers with NYNEX but dial out through the CLEC.

But number portability was only one giant hurdle. The other major hurdle was the termination rate (often called reciprocal compensation rate) the ILECs wanted to charge the CLECs to terminate their local traffic to the ILECs customers.

The ILECs sought to charge the CLECs the same rates the ILECs charged long distance carries (or IXCs) for switched access. The problem here was that the switched access rates ILECs wanted to charge the CLECs were actually higher than the retail rates the ILECs charged their own customers for local calls. Obviously, it’s hard to break into a market by charging your prospective customer a higher rate than what they’re currently paying. So the CLECs faced an unwinnable price squeeze UNLESS they could get the regulators to agree to a different termination or reciprocal compensation rate. The CLECs asked regulators for Bill & Keep, meaning we each bill our customers for the traffic they send and we keep the revenue.

The ILECs rejected Bill & Keep in its entirety because they knew the traffic was completely unbalanced with CLECs sending traffic but receiving very little. You might ask why the CLECs couldn’t balance the traffic. Recall above that number portability or LNP didn’t yet exist and customers like Merrill, Goldman, Fidelity, etc., didn’t want to change their numbers which often times would have required changing the area code. So CLECs sent traffic but received very little.

The ILECs told the CLECs that this was not their problem. The simple ILEC response was, balance the traffic, meaning send us the same amount (or send us more, ha hah) as you receive, and the termination or reciprocal compensation rate won’t matter.

So the CLECs were in a pickle, facing price squeezes in markets where state regulators had not adopted Bill & Keep. The CLECs had to fight these reciprocal compensation battles asking for Bill & Keep or more reasonable termination rates state by state with very uncertain outcomes.

THIS IS WHERE IT GETS FUN

At this point in our story, around 1996, MFS had been acquired by Worldcom. Shortly after Worldcom purchased MFS, Worldcom acquired ISP UUNET. UUNET had a lot of dial-up internet traffic. (Remember those days?)

All of the sudden MFS gave UUNET a bunch of DIDs (essentially phone numbers) and the balance of traffic changed dramatically. Why? All of the dial-up customers got their dial tone from the ILEC but all of the sudden the CLECs started selling DIDs to the ISPs. So the ILEC end users surfing the internet would send traffic to the ISP which were customers of the CLECs. Pretty soon the balance of traffic swung wildly in favor of the CLECs. This is because the average length of voice calls were about 4 minutes while the average length of dial-up internet session was hours (especially after ISPs started offering a flat rate unlimited usage).

Well, as noted at the beginning of this story when the ILECs started getting their recip comp bills from the CLECs, they freaked the F$%^ out and ran to the regulators crying foul, ignoring, of course, that they had essentially dared and taunted the CLECs into changing the balance of traffic.

Of course, the regulators found a way to somehow parse the call flow of these internet calls in a way where the ILECs escaped the 10s (if not 100s) of millions CLECs were billing the ILECs.

Fast forward to 2014 and the topic of Rob’s post and the issue of IP traffic asymmetry. My warning to Verizon and Comcast is to be very careful what you wish for and who you taunt. Just as CLECs found a solution to the balance problem, today’s ISPs may too.